Vesuvius Challenge 2023 Grand Prize awarded: we can read the first scroll!

We’re announcing the winners of the Vesuvius Challenge 2023 Grand Prize. We’ll look at how they did it, what the scrolls say, and what comes next.

Join us for a celebration at the Getty Villa Museum in Los Angeles on March 16th, 4pm. More information here.

Victory

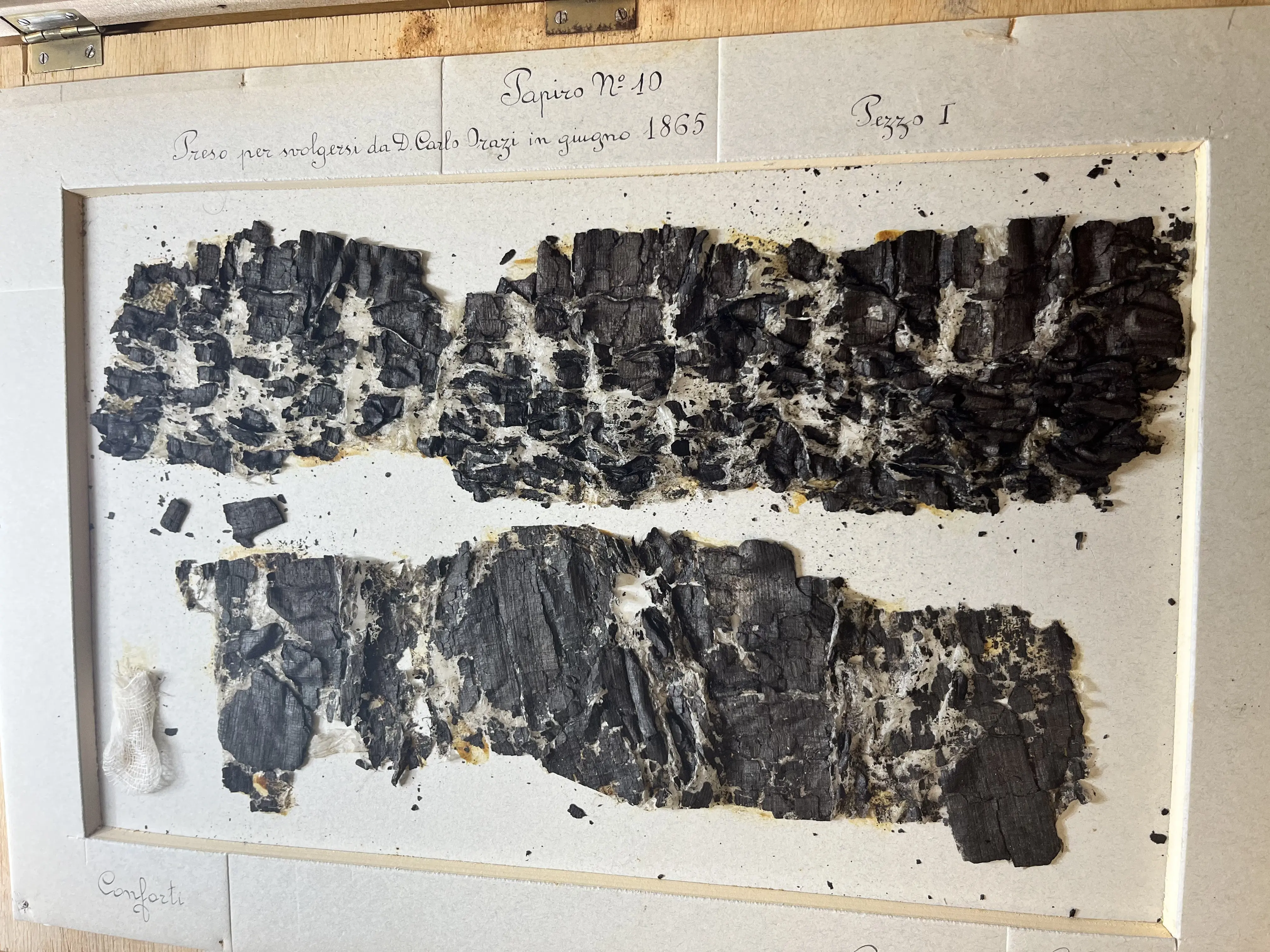

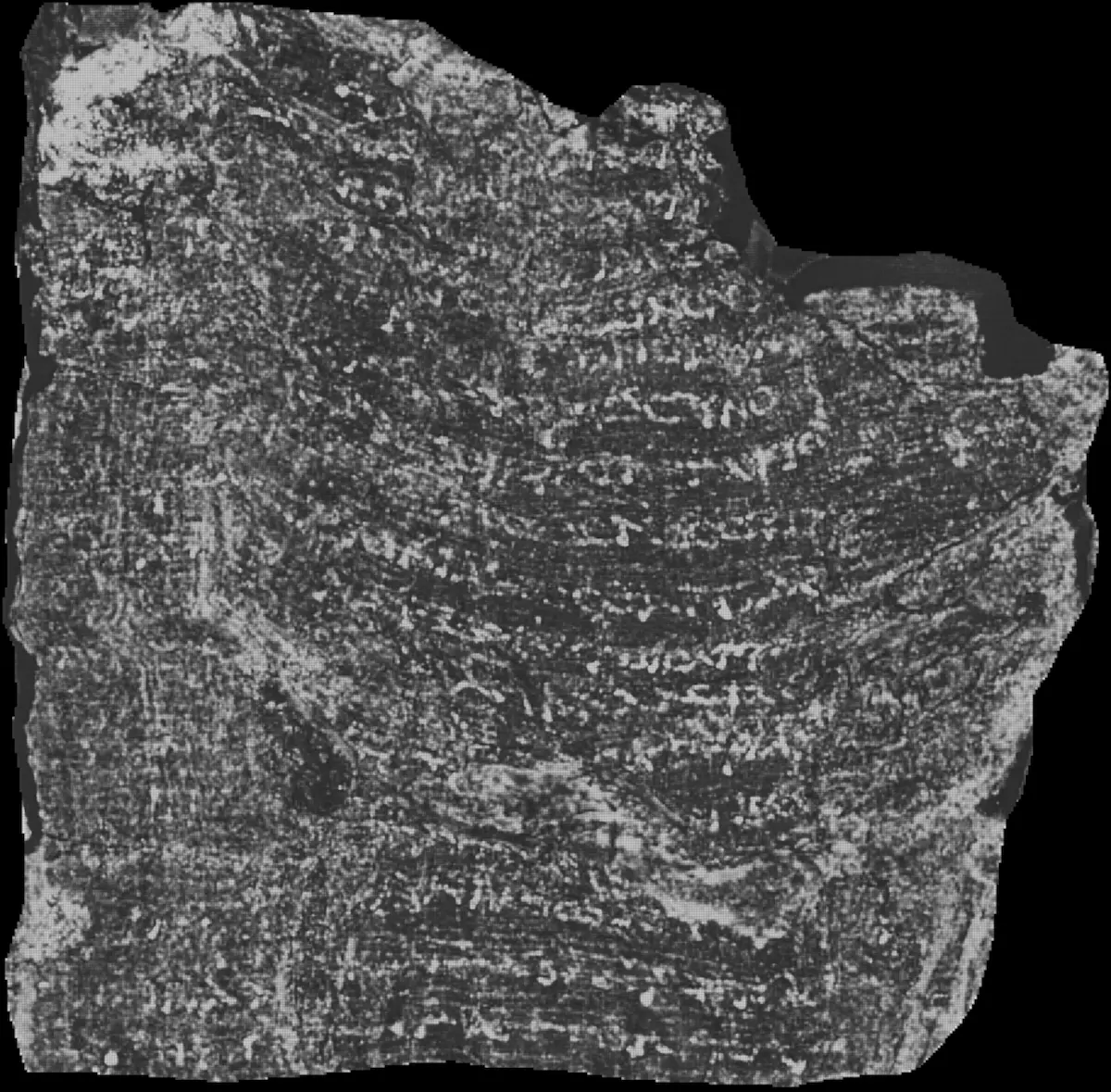

Two thousand years ago, a volcanic eruption buried an ancient library of papyrus scrolls now known as the Herculaneum Papyri.

In the 18th century the scrolls were discovered. Hundreds of them are now stored in a library in Naples, Italy; these lumps of carbonized ash cannot be opened without severely damaging them. But how can we read them if they remain rolled up?

On March 15th, 2023, Nat Friedman, Daniel Gross, and Brent Seales launched the Vesuvius Challenge to answer this question. Scrolls from the Institut de France were imaged at the Diamond Light Source particle accelerator near Oxford. We released these high-resolution CT scans of the scrolls, and we offered more than $1M in prizes, put forward by many generous donors.

A global community of competitors and collaborators assembled to crack the problem with computer vision, machine learning, and hard work.

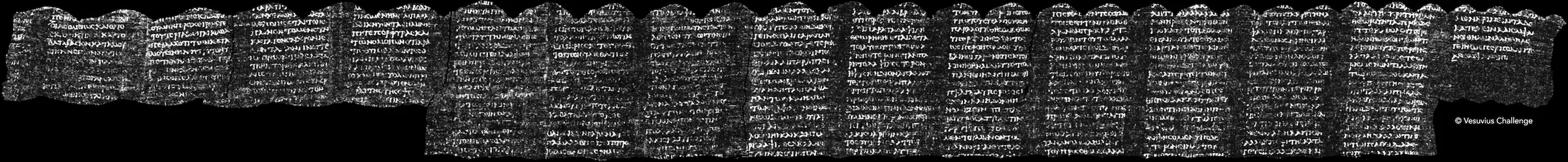

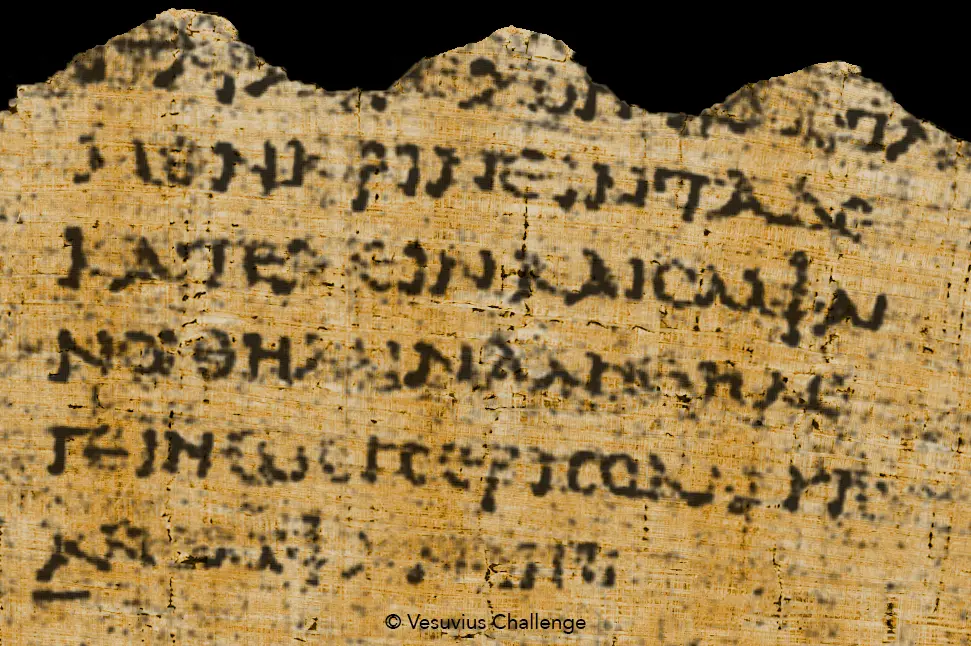

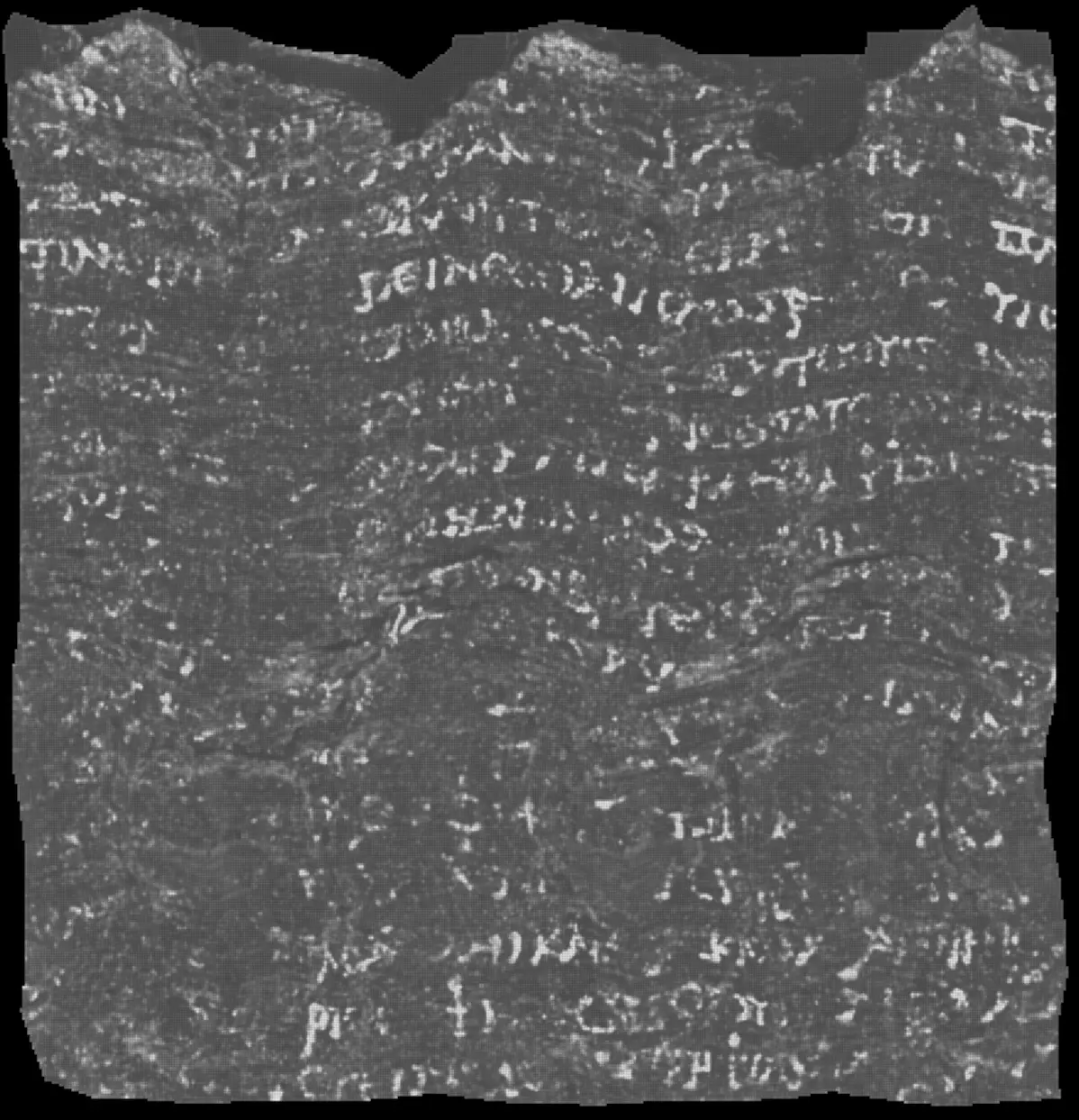

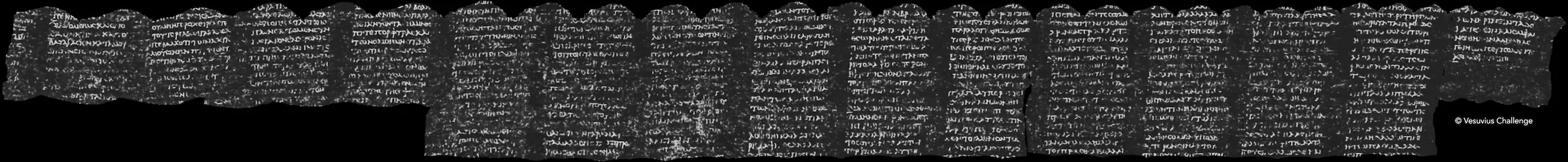

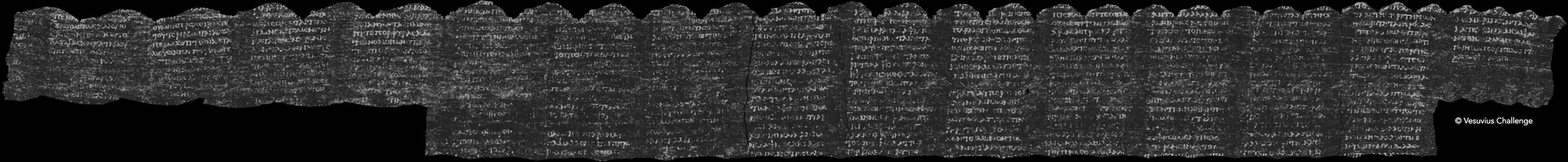

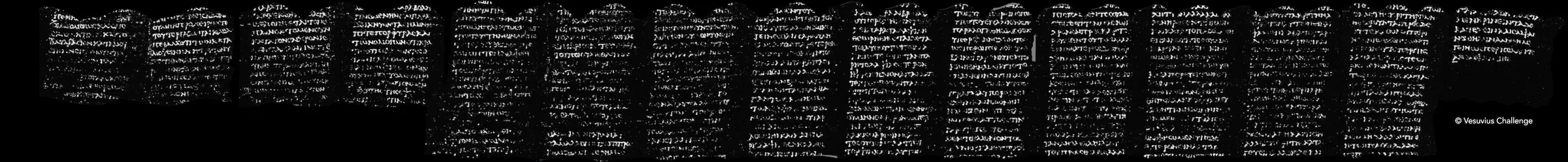

Less than a year later, in December 2023, they succeeded. Finally, after 275 years, we can begin to read the scrolls:

The thoughts of our ancestors, locked in mud and ash for 2000 years, hidden in darkness — now, with the light of a worldwide effort shining upon them, finally seen again.

Grand Prize

We received many excellent submissions for the Vesuvius Challenge Grand Prize, several in the final minutes before the midnight deadline on January 1st.

We presented these submissions to the review team, and they were met with widespread amazement. We spent the month of January carefully reviewing all submissions. Our team of eminent papyrologists worked day and night to review 15 columns of text in anonymized submissions, while the technical team audited and reproduced the submitted code and methods.

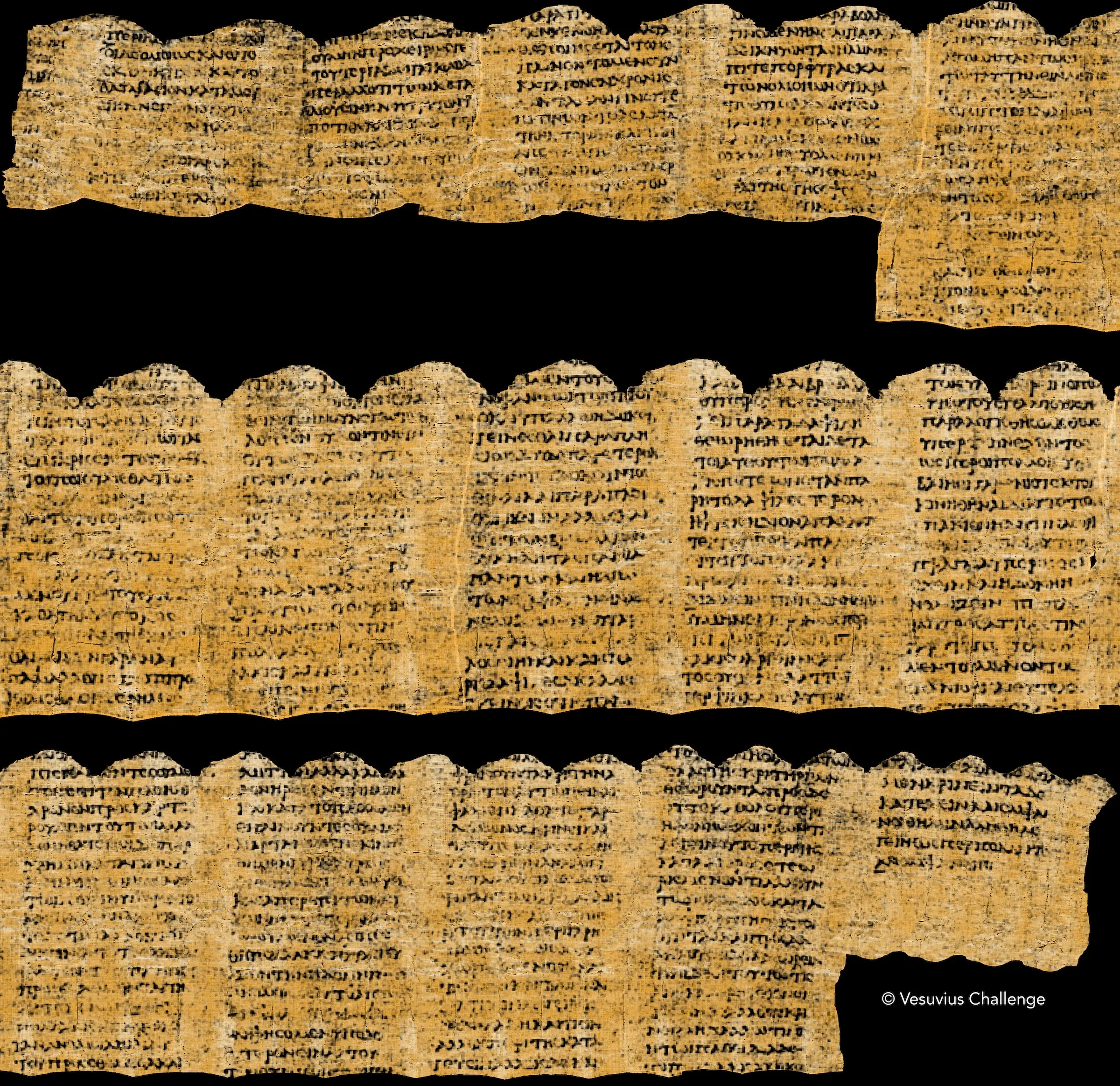

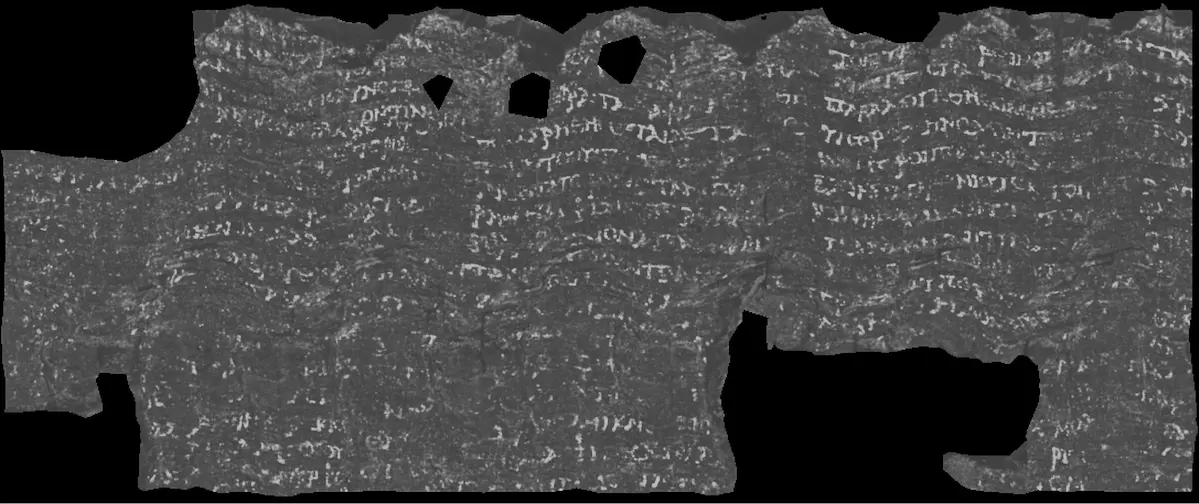

There was one submission that stood out clearly from the rest. Working independently, each member of our team of papyrologists recovered more text from this submission than any other. Remarkably, the entry achieved the criteria we set when announcing Vesuvius Challenge in March: 4 passages of 140 characters each, with at least 85% of characters recoverable. This was not a given: most of us on the organizing team assigned a less than 30% probability of success when we announced these criteria! And in addition, the submission includes another 11 (!) columns of text — more than 2000 characters total.

The results of this review were clear and unanimous: the Vesuvius Challenge Grand Prize of $700,000 is awarded to a team of three for their excellent submission. Congratulations to Youssef Nader, Luke Farritor, and Julian Schilliger!

All three winning team members have been strong community contributors since the very beginning of Vesuvius Challenge. You may remember Youssef. He is the Egyptian PhD student in Berlin who was able to read a few columns of text back in October, winning the second-place First Letters Prize. His results back then were particularly clear and readable, which made him the natural lead for the team that formed.

You might remember Luke as well: he is the 21-year-old college student and SpaceX intern from Nebraska, who was the first person in history to read an entire word from the inside of a Herculaneum scroll (ΠΟΡΦΥΡΑϹ, “purple”). This won him the first-place First Letters Prize, a few weeks before Youssef’s results.

And finally, you might remember Julian. He is the Swiss robotics student at ETH Zürich, who won three Segmentation Tooling prizes for his incredible work on Volume Cartographer. This enabled the 3d-mapping of the papyrus areas you see before you.

For the Grand Prize, they assembled into a superteam, crushing it by creating what was unanimously deemed the most readable submission.

The submission contains results from three different model architectures, each supporting the findings of the others, with the strongest images often coming from a TimeSformer-based model. Multiple measures prevent overfitting and hallucination, including results from multiple architectures, a study across input/output window sizes, label smoothing, and varying validation folds. Like with all our prizes, this ink detection code has been made public as open source (on GitHub), leveling up everyone in the community.

In addition to unparalleled ink detection, the winning submission contained the strongest auto-segmentation approach we have seen to date (more about the process of “segmentation” below). ThaumatoAnakalyptor (roughly: Miracle Uncoverer) by Julian generates massive papyrus segments from multiple scrolls. Re-segmentations of well known areas validate previous ink findings, and entirely new segmentations reveal writing elsewhere, such as the outermost wrap of the scroll!

Congratulations to Youssef, Luke, and Julian. You are the well-deserved winners of the 2023 Vesuvius Challenge Grand Prize!

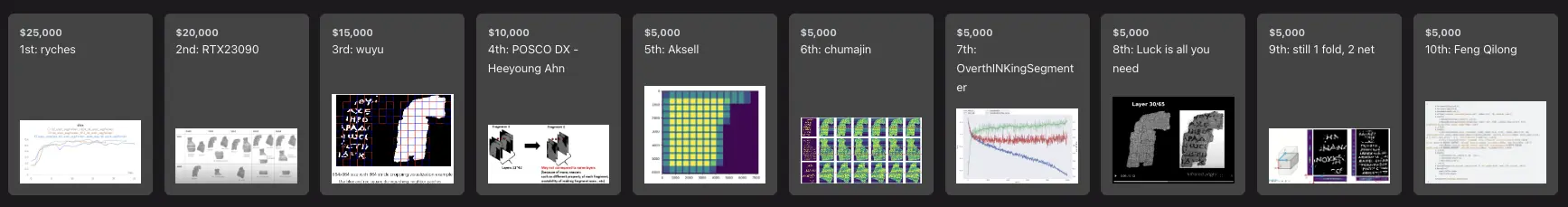

Runners up

Of the remaining submissions, the scores from our team of papyrologists identify a three-way tie for runner up. These entries show remarkably similar readability to each other, but still stand out from the rest by being significantly more readable. Congratulations to the following teams, each taking home $50,000!

These teams each brought to the table new approaches to the subtleties of ink labeling and sampling. Be sure to check out their methods at the links above. Other teams may also now choose to share their approaches, so be sure to follow our Discord community for updates. Joining our community also provides access to the CT data and more images under our data agreement, as well as a front-row seat to daily discovery and collaboration!

What does the scroll say?

To date, our efforts have managed to unwrap and read about 5% of the first scroll. Our eminent team of papyrologists has been hard at work and has achieved a preliminary transcription of all the revealed columns. We now know that this scroll is not a duplicate of an existing work; it contains never-before-seen text from antiquity. The papyrology team are preparing to deliver a comprehensive study as soon as they can. You all gave them a lot of work to do! Initial readings already provide glimpses into this philosophical text. From our scholars:

Philodemus, of the Epicurean school, is thought to have been the philosopher-in-residence of the villa, working in the small library in which the scrolls were found.

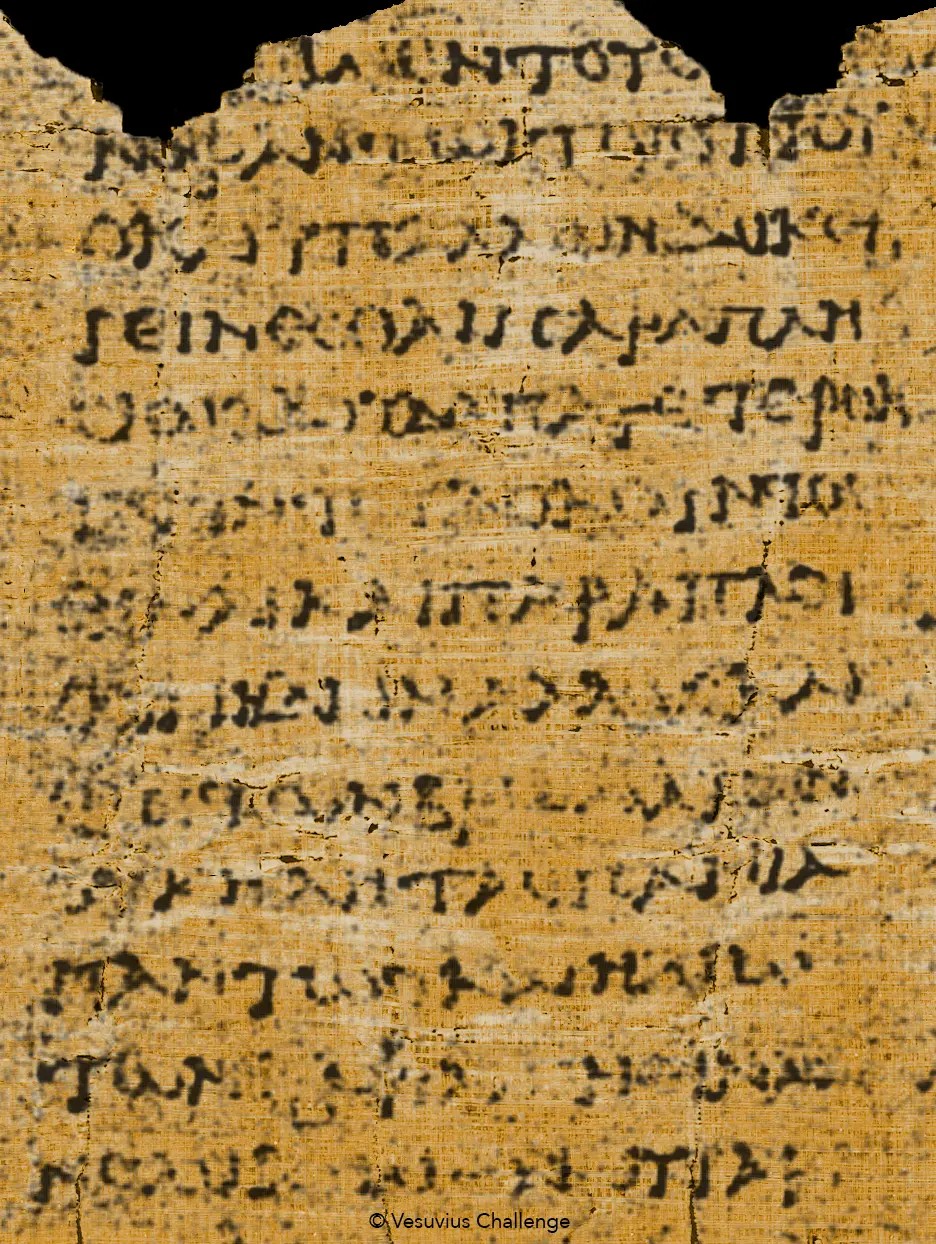

Initial, rough draft transcriptions:

col. -8, ll. 2-14:

2 ...]ι̣μ̣εν τοὺϲ̣ [πα]ρ̣[ὰ Ξ]ε̣-

νοφάντωι το̣ιούτου[ϲ,

ὃ καὶ ὑπ’ ἄ̣λλων δοκεῖ

5 γείνεϲθαι, παραπλη-

ϲίωϲ δ̣’ ο̣ὐδὲ παρ̣’ ἑτέρωι

ἴδι̣ον το̣ῦ δ̣οκοῦ̣ντοϲ̣

εἶναι καὶ παρὰ πλε̣ί-

οϲ̣ι̣ν̣ ἥδιο̣ν, ἀλλ’ ὡ̣ϲ̣ καὶ

10 ἐ̣π̣ὶ τῶν βρω̣μ̣άτ̣ων

ο̣ὐ̣κ ἤδ̣η τὰ ϲπάνια

πάντωϲ̣ καὶ ἡδ̣ίω

τῶν δ̣αψιλῶν̣ ε̣ἶναι̣

14 νομίζ̣ο̣με̣ν· οὐ γ̣ὰρ̣

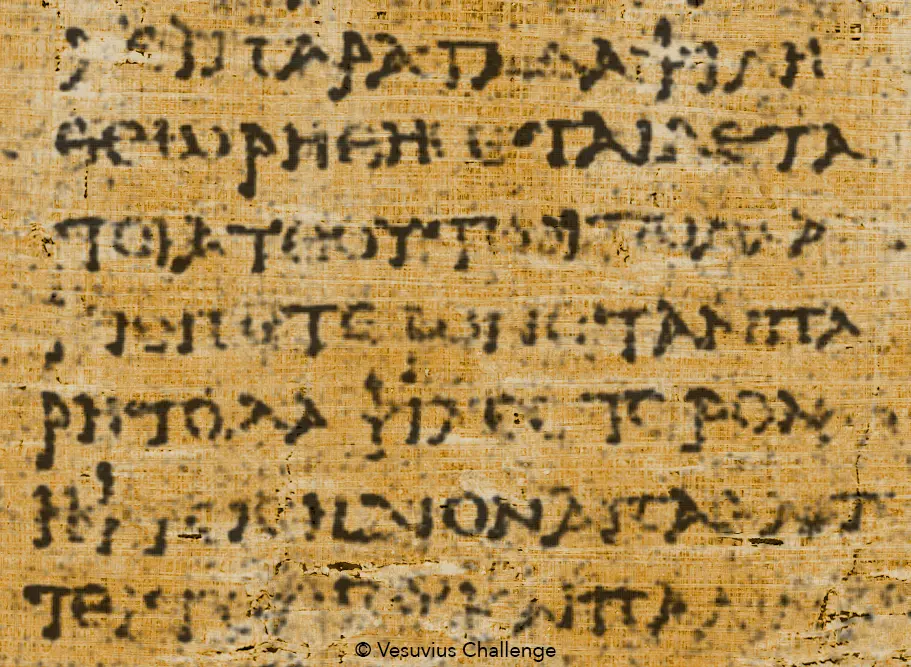

col. -7, ll. 4-10:

λ̣ει παρὰ τὰ δαψιλῆ.

5 θεωρηθήϲεται δὲ τὰ

τοιαῦθ’ οὕτω{ι} πολ̣λά-

κιϲ πότερον ὅ̣ταν πα-

ρῇ τὸ δαψιλέϲτερον

ἡ φύϲιϲ ἥδιον ἀπαλλάτ-

10 τει το̣ύ̣τ̣ο̣υ̣ καὶ πάλ̣ι̣ν̣ ̣ ̣

Later in the scroll:

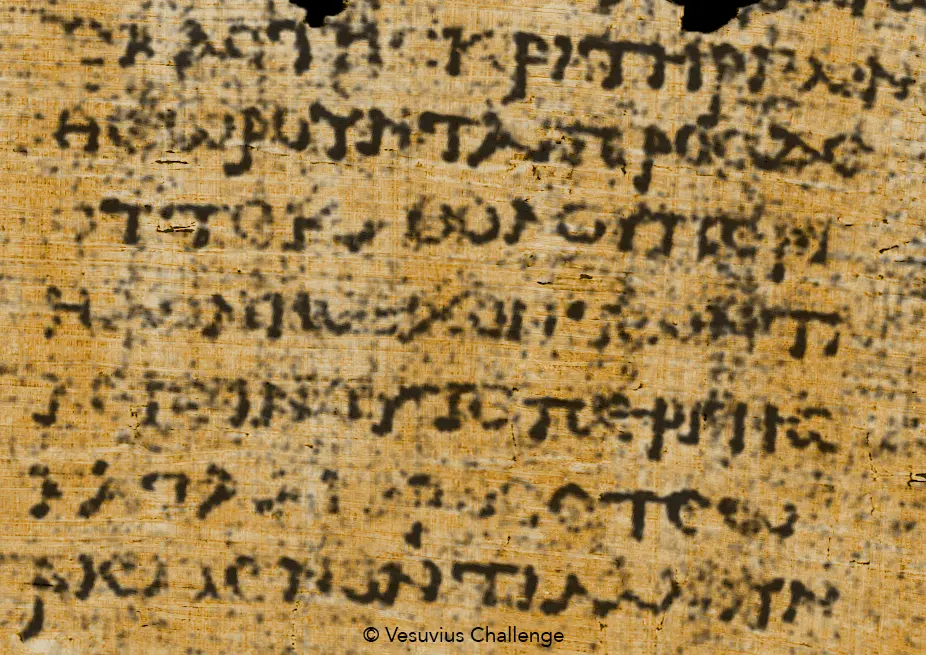

col. -2, ll. 2-8:

2 ἑ̣κάϲτηϲ κριτηρίων

θεωροῦνται. πρὸϲ δὲ

οὔτε καθόλου περὶ

5 ἡδονῆϲ ἐχόντων τι

λέγειν οὔτε περὶ τῆϲ

κατὰ μ̣έ̣ρο̣ϲ̣, ὅ̣τε ὡ-

8 ριϲμένον τι, ἀλλ’ οὖν

…

Finally the scroll concludes:

col. -1, ll. 1-6:

1 ὰρ ἀπ̣εχόμ̣ε̣θ̣α̣ τὰ

μὲν κρίνειν, τὰ δὲ

κατέχειν καὶ ἐμφαί

νoιθ’ ἡμῖν ἀληθῆ λέ-

5 γειν ὥϲπερ πολλά̣κιϲ

ἂν ἐ̣μφανε̣ίη̣{ι}.

Richard Janko writes:

Federica Nicolardi told us:

From Bob Fowler:

Scholars might call it a philosophical treatise. But it seems familiar to us, and we can’t escape the feeling that the first text we’ve uncovered is a 2000-year-old blog post about how to enjoy life. Is Philodemus throwing shade at the stoics in his closing paragraph, asserting that stoicism is an incomplete philosophy because it has “nothing to say about pleasure?” The questions he seems to discuss — life’s pleasures and what makes life worth living — are still on our minds today.

We can expect many more works from Philodemus in the current collection, once we’re able to scale up this technique. But there could be other text as well — an Aristotle dialog, a lost history of Livy, a lost Homeric epic work, a poem from Sappho — who knows what treasures are hidden in these lumps of ash.

And there is the hope of a much bigger library still in the ground, since two levels of the villa remain unexcavated. More about this below!

How accurate are these pictures?

Machine learning models are infamous for “hallucinating”: making up text or pictures that look similar to their training data. Similarly, there might be ways for contestants to cheat by making up images themselves, e.g. by embedding those in the model weights. How do we know that that’s not happening here? There are a couple of answers:

- Technical reproduction. The Vesuvius Challenge Technical Review Team reproduced the winning submissions manually. We made sure to clearly understand every part of the code, and that when we run it independently we get similar output images. Since all code and training data is now open source, you can do the same!

- Multiple submissions of the same area. You might have noticed that all submission images above show the same area of the scroll. This is because we released 3d-mapped papyrus sheets within the CT-scan (“segments”) created by our segmentation team, which were then used by all contestants. The resulting output images — created by different ML models and training labels — have produced extremely similar results. This holds not just for the winners and runner ups, but also for the other submissions that we received.

- Small input/output windows. The ink detection models are not based on Greek letters, optical character recognition (OCR), or language models. Instead, they independently detect tiny spots of ink in the CT scan, the writing appearing later when these are aggregated. As a result, the text appearing in the images is not the imagined output of a machine learning model, but is instead directly tied to the underlying data in the CT scan.

How does the unwrapping work?

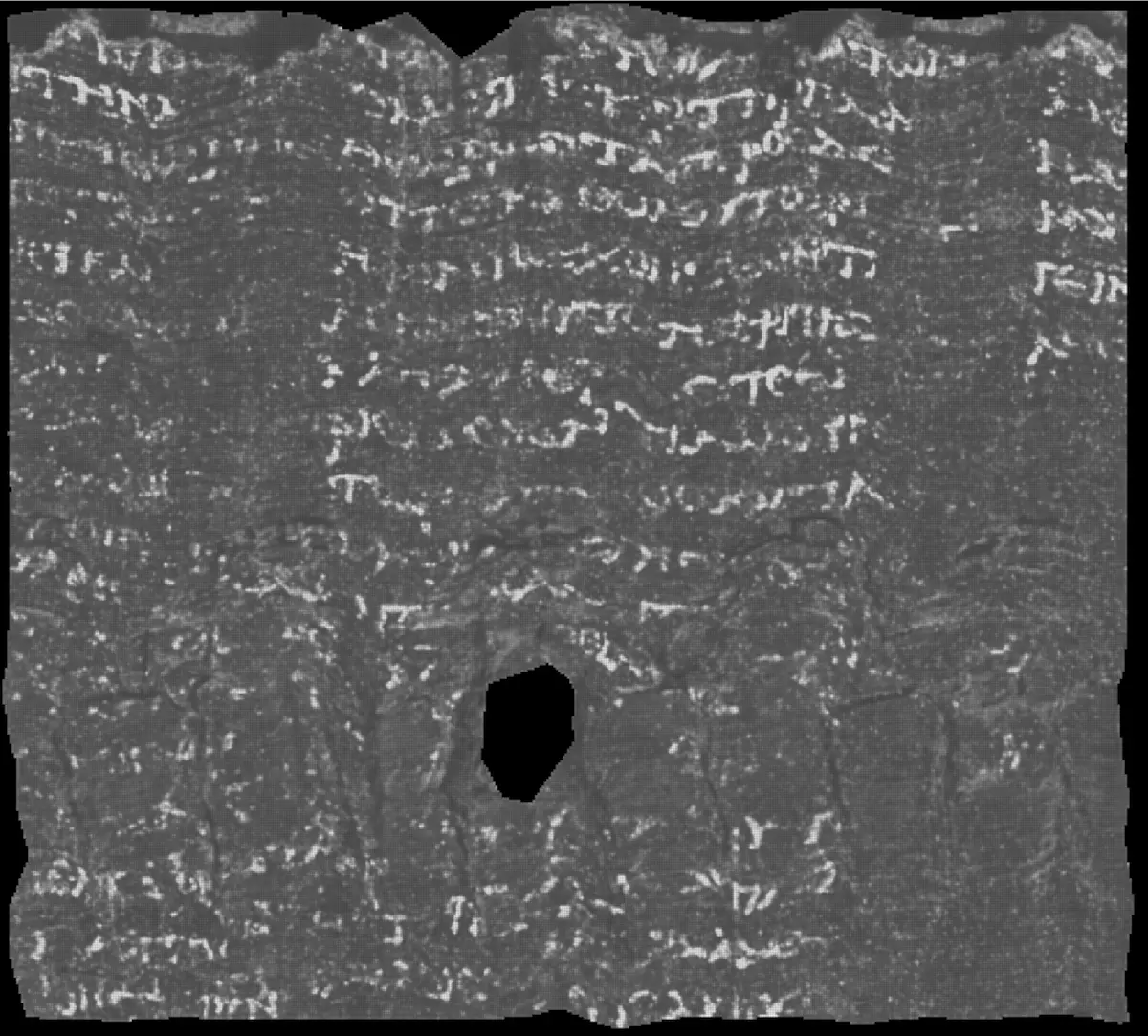

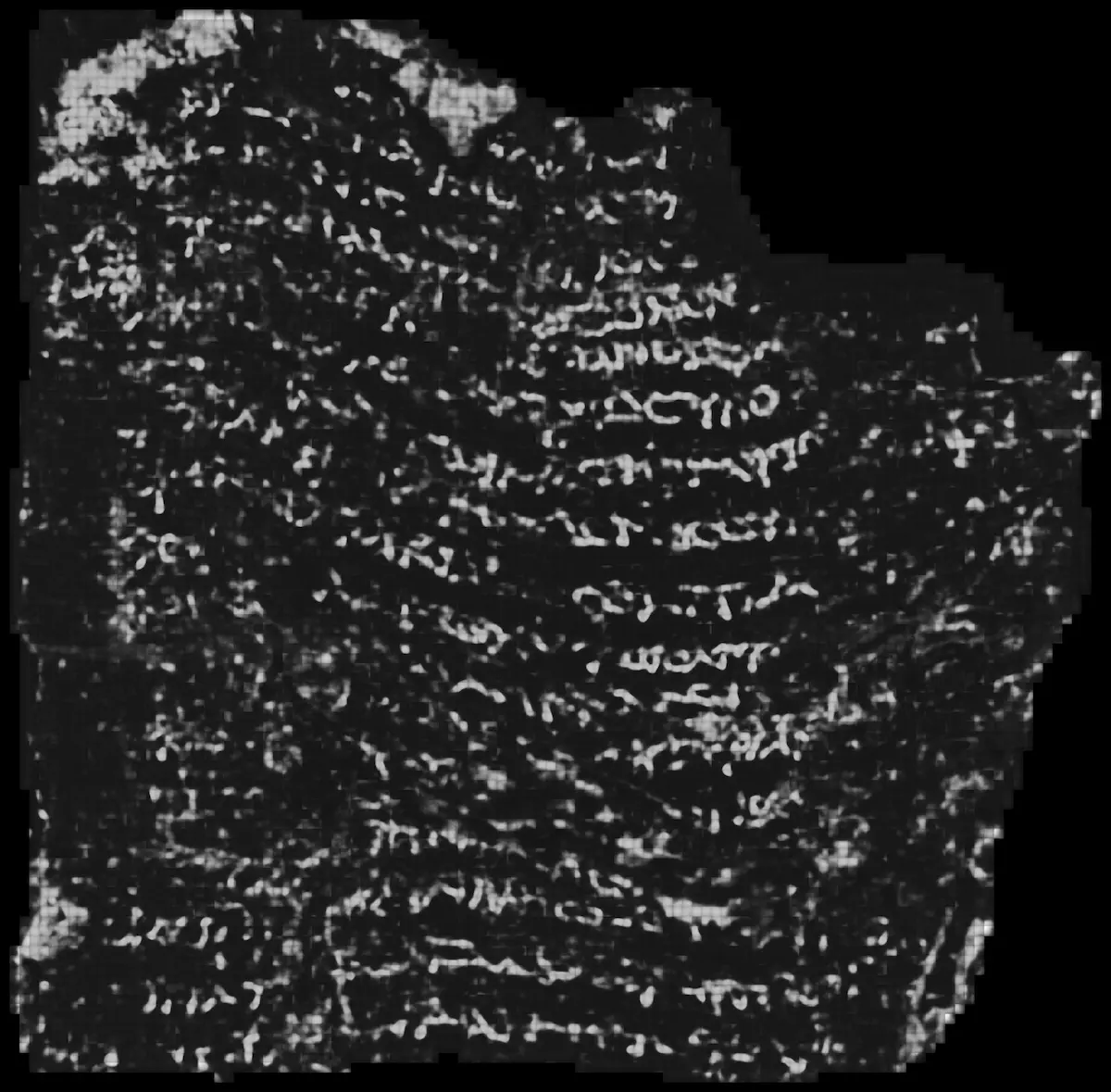

- Scanning: creating a 3D scan of a scroll or fragment using X-ray tomography.

- Segmentation: tracing the crumpled layers of the rolled papyrus in the 3D scan and then unwrapping, or flattening, them.

- Ink Detection: identifying the inked regions in the flattened segments using a machine learning model.

These scrolls were scanned at Diamond Light Source, a particle accelerator near Oxford, England. The facility produces a parallel beam of X-rays at high flux, allowing for fast, accurate, and high-resolution imaging. The X-ray photos are turned into a 3D volume of voxels using tomographic reconstruction algorithms, resulting in a stack of slice images.

The next step is to identify individual sheets of papyrus in 3D space. For this we primarily use a tool called Volume Cartographer, created by Seth Parker and others in Brent Seales’ lab, and augmented by our contestants, primarily Julian Schilliger (Grand Prize winner) and Philip Allgaier.

Volume Cartographer is operated by our team of full-time segmenters: Ben Kyles, David Josey, and Konrad Rosenberg. They use a combination of automatic algorithms and manual adjustments to map out large areas of papyrus. This is still a painstaking process, with lots of room for improvement if we’re going to segment all the scrolls.

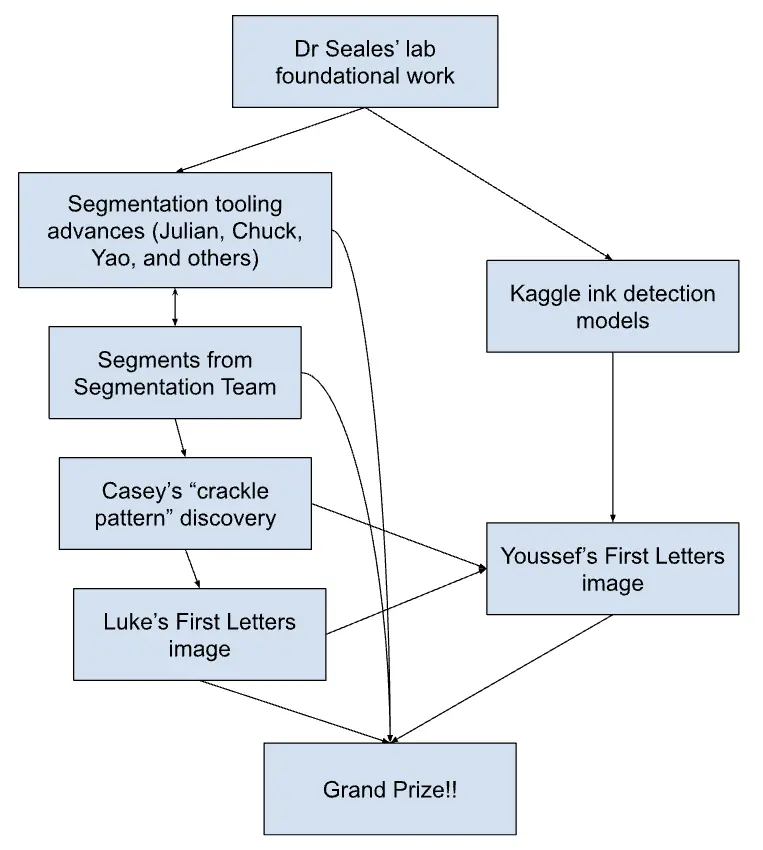

Finally, ink detection. Stephen Parsons at Brent’s lab had shown that Herculaneum ink could theoretically be detected in CT scans, but so far only using smaller fragments — detecting ink in the larger scans of complete scrolls had yet to be achieved. For months this part proved elusive, until progress was made on two separate tracks:

- Crackle pattern. Last summer, Casey Handmer discovered a strange pattern of “crackle” by looking at raw flattened surface volumes. This pattern appeared to form letters. Casey won the First Ink Prize for this monumental discovery and shared it with the community, and a flurry of activity followed.

- Kaggle competition. Separately, hundreds of teams tried building the best machine learning model for detecting ink in open fragments — pieces that had broken off during the physical unrolling process of scrolls, hundreds of years ago. Instead of labeling crackle (which wasn’t known yet), they had the benefit of ground truth data directly from photos of these fragments.

After the success of the First Letters Prize, the Grand Prize seemed within reach. Youssef, Luke, and Julian teamed up, with several other teams putting in strong submissions as well.

What did it take?

With Vesuvius Challenge, we hope not only to solve the problem of reading the Herculaneum Papyri, but also to inspire similar projects. For that, it’s helpful to know what has contributed to our success in 2023. Here are some things we believe were important:

- An inspiring goal and a clear target. There are many worthy causes in the world, so it helps that our goal is unusual for a computing competition. It drew more press and donations early on, it attracted an intrinsically motivated community, and it increased our probability of success to begin with (emerging research area => a higher marginal utility of dollars spent). We’d love to see more projects that are “out there,” for exactly these reasons!

- A solid starting point. The foundation was laid by Dr. Seales and his team. They spent two decades making the first scroll scans, building Volume Cartographer, demonstrating the first success in virtual unwrapping, and proving that Herculaneum ink can be detected in CT.

- Blending competition and cooperation. A Grand Prize on its own would suffer from information “hoarding”: no one would share their intermediate work, because others could take it and use it to beat them to the finish line. Without information sharing, the probability of a single team solving all the puzzle pieces to win the Grand Prize would be dramatically lower.

- Hiring an in-house segmentation team. Every week we asked ourselves: what is the best thing we can do now to maximize the chance that someone wins the Grand Prize? In early summer, this led to the (then somewhat controversial) decision of hiring a full-time team of data labelers to manually trace the papyrus inside the scrolls and open source the flattened segments.

- Maximizing surface area for breakthroughs. Our success was the result of many smaller breakthroughs by a broad group of people. It’s remarkable how many things had to come together to make this happen. Remove any of these, and we would not have succeeded, at least not within this timeframe.

What’s next? Announcing the 2024 Vesuvius Challenge Grand Prize.

When we started the competition, most of us estimated that we had a less than 30% probability of success within the year. At that point, no letters had yet been discovered inside of a scroll. On top of that, the scrolls had barely been segmented at all. We had doubt as to whether the project could succeed, especially by the deadline we set. Was the ink signal present? Were the scans high-resolution enough? Could the techniques used to identify ink in the fragments be transferred into a scroll? None of this was known at the time. But we knew it was worth trying!

In Stage 1 of Vesuvius Challenge, we answered all of these questions, extracting 15 columns of never-before-seen text from inside a lump of carbon. We now have proven techniques for virtually unwrapping the papyrus scroll and recognizing ink using machine learning.

Vesuvius Challenge Stage 2

In 2023 we got from 0% to 5% of a scroll. In 2024 our goal is to go from 5% of one scroll, to 90% of all four scrolls we have scanned, and to lay the foundation to read all 300 scrolls.

The primary goal for 2024 is to read 90% of the scrolls, and we will issue the 2024 Grand Prize to the first team that is able to do this. More details on the exact grand prize judging criteria will be available in March.

The bottleneck to achieve this milestone is the process of tracing the surface of the papyrus inside the scroll. Today this is extremely manual. It cost us more than $100 per square centimeter in manual labor to produce the text we can read today. At this price, it would cost hundreds of millions or maybe even billions of dollars to segment all of the scrolls. While improvements to our segmentation tools have increased our efficiency, it is still far too manual and expensive. What we need is automation.

And so our primary goal for stage 2 is to perfect autosegmentation. Done right, this will also allow us to read the most challenging regions within the scroll – areas where the scroll was heavily compressed, cracked, delaminated, or otherwise damaged – which in many cases our current tools cannot even penetrate.

In 2023 we were amazed by the community contributions. We loved the competition for the grand prize, which brought out the best in the contestants, but we were also thrilled to see the community collaborate towards intermediate goals. In 2024 we are leaning into that, still offering a grand prize, but allocating even more of the prize pool towards community contributions – a pool that will grow as we raise more money.

We’re also planning to help speed things along ourselves, balancing prizes and in-house expertise to continue the collaboration that worked so well in 2023. To this end, we’ll hire a small software/ML team, in addition to the full-time segmentation team, who will work in the open with our community to advance the state of the art.

If you are interested in contributing to our funding, and joining the craziest archeological project in existence, please contact us.

And after that?

After that, we will scan and read every scroll. We estimate that the scrolls we have in Naples contain more than 16 megabytes of text. Some members of our papyrology team say that revealing this text will be the greatest revolution in the classics since the Renaissance. However it goes, it will certainly be fun to try!

And as if the prospect of reading hundreds of scrolls isn’t good enough, there might be an even bigger payoff at the end of all of this (as Nat said on the Dwarkesh podcast: “there is gold in this mud”).

The potential of tens of thousands of scrolls, still buried, waiting to be discovered?! The most exciting days still lay ahead.

Read more detail about what comes next in our Master Plan.

Thank you

- Everyone who competed, shared insights, wrote code, made analyses, and brought energy to the project.

- Our adventurous donors, all of whom are private individuals from the tech world, who supported this project when it was not at all clear that there was any chance of success.

- The organizing teams (listed on our homepage): Vesuvius Challenge team, EduceLab team, and Papyrology team.

- Our partners: EduceLab, Institut de France, Diamond Light Source, Biblioteca Nazionale di Napoli, the Getty, and Kaggle — and all their respective funders.

- The professional and amateur papyrologists, historians, classicists, and other scholars — who helped answer countless questions in Discord.

- The supporting staff on the Vesuvius Challenge side (Sean, Emily, Frank, Lulu), and on the University of Kentucky side (Lindsey, Eric).

- The many contributors to the cause who came before us — who did excavations, wrote code, made scans, and built machines out of catgut and pig bladders to try to physically unroll the scrolls.

- And of course the Grand Prize winners!

Thank you all so much!!

Now let’s get on with it and read the rest of the scrolls. The best is yet to come.

Join us for a celebration at the Getty Villa Museum in Los Angeles on March 16th, 4pm. More information here.