First word discovered in unopened Herculaneum scroll by 21yo computer science student

Code is on Github: Luke, Youssef.

The Herculaneum papyri, ancient scrolls housed in the library of a private villa near Pompeii, were buried and carbonized by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD. For almost 2,000 years, this lone surviving library from antiquity was buried underground under 20 meters of volcanic mud. In the 1700s, they were excavated, and while they were in some ways preserved by the eruption, they were so fragile that they would turn to dust if mishandled. How do you read a scroll you can’t open? For hundreds of years, this question went unanswered.

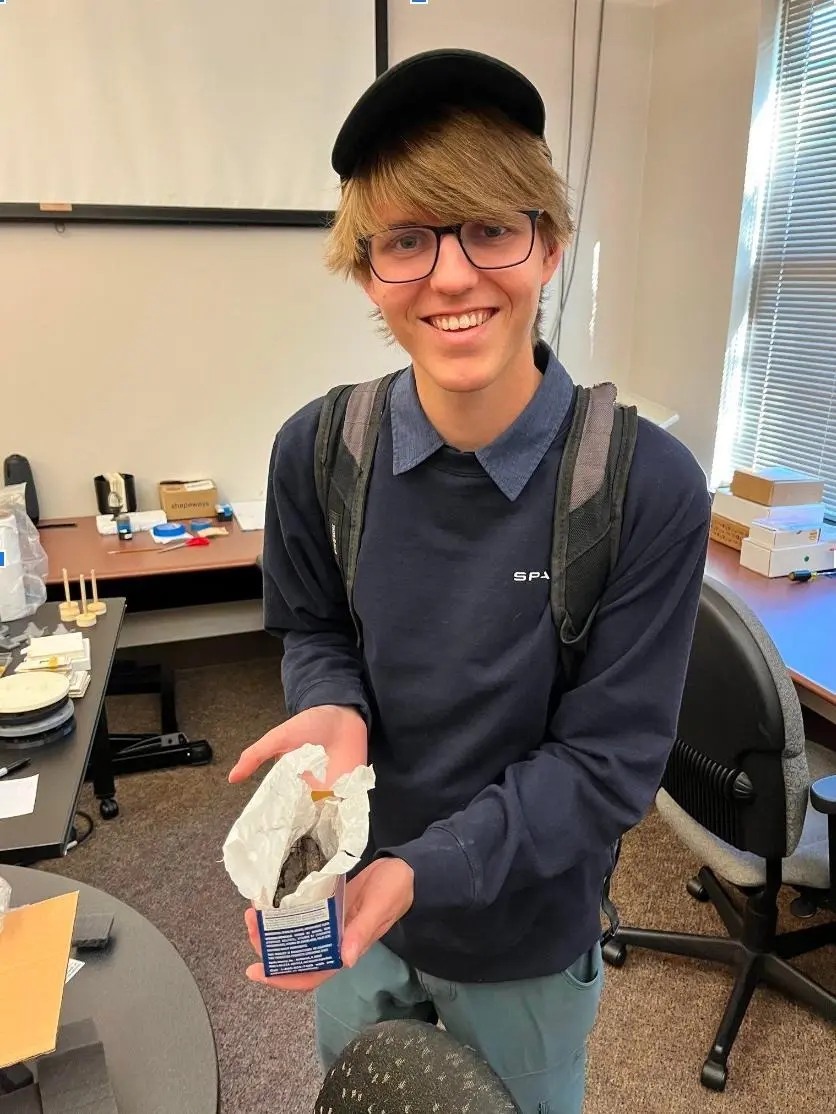

That is until Luke Farritor, a contestant of the Vesuvius Challenge, became the first person in two millennia to see an entire word from within an unopened scroll this August. For that, we are thrilled to award Luke a $40,000 First Letters Prize, which required contestants to find at least 10 letters in a 4 cm2 area in a scroll.

Shortly after that, another contestant, Youssef Nader, independently discovered the same word in the same area, with even clearer results — winning the second place prize of $10,000.

These breakthroughs were both inspired by contestant Casey Handmer, who was the first person to find substantial, convincing evidence of ink within the unopened scrolls, as explained in his blog post and this video. His insights led directly to Luke’s discovery, as well as an improved understanding of the ink signal. We’re awarding him a $10,000 First Ink Prize. Congratulations to Casey, Luke, and Youssef!

So how did we get here, and how do these models work? Let’s start with a little history.

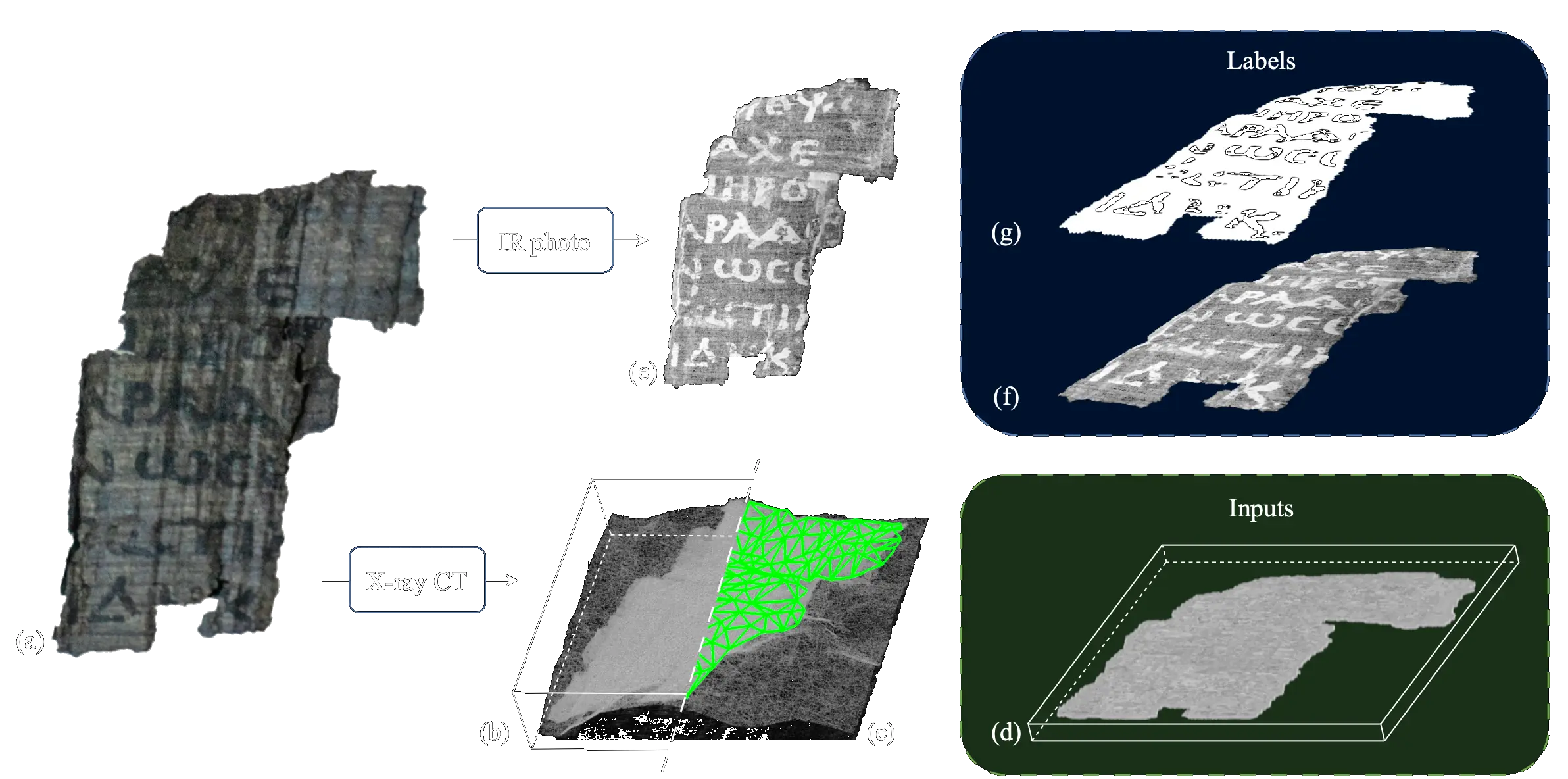

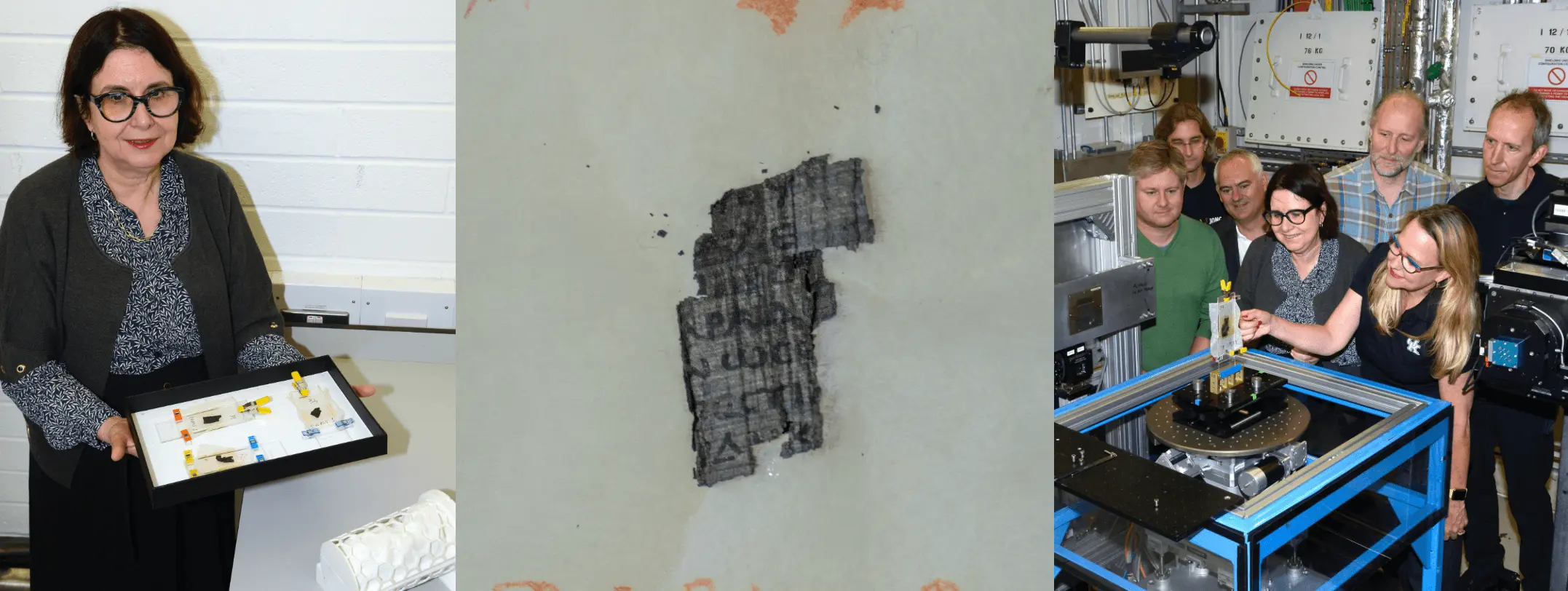

EduceLab scans

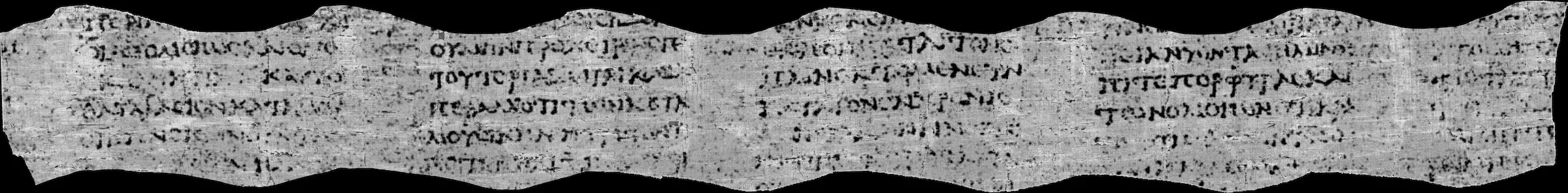

Our story starts in 2019, when professor Brent Seales at the University of Kentucky’s EduceLab imaged Herculaneum scrolls in a particle accelerator, generating 3D CT-scans at resolutions as high as 4 µm.

His team also scanned and photographed detached scroll fragments bearing visible ink, thus providing a ground truth dataset.

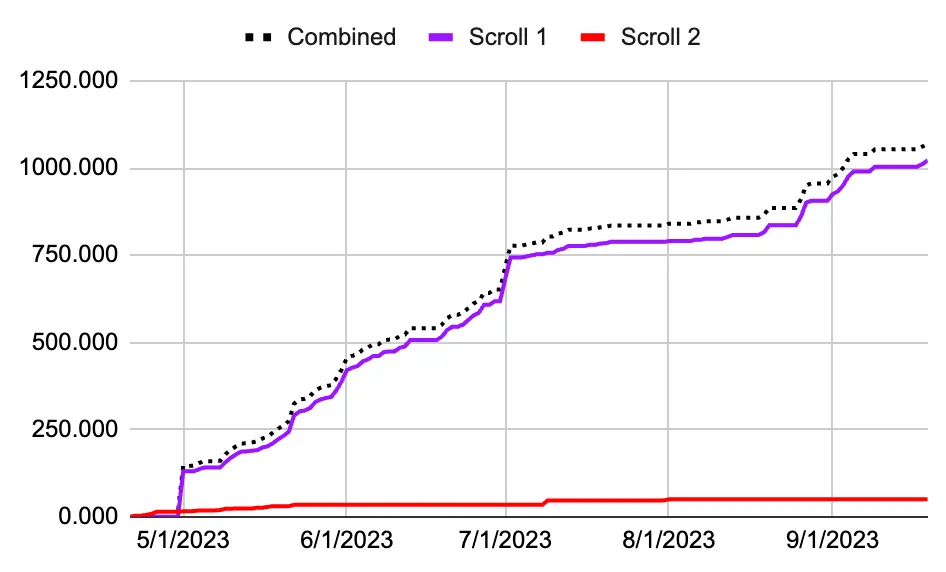

Professor Seales’ graduate student, Stephen Parsons, worked on detecting ink from the CT-scans using machine learning models and found success with the detached fragments. That success caught the eye of tech entrepreneurs Nat Friedman and Daniel Gross, who started Vesuvius Challenge to accelerate this progress. They launched an open competition March of 2023, and — alongside a $700,000 Grand Prize — awarded several smaller prizes for the development of open source tools and techniques.

Early in the summer, a small team of annotators (the “segmentation team”) joined our effort. They began mapping the 3D structure of the scroll using tools initially built by EduceLab and improved by our community. By July we had segmented and “virtually flattened” hundreds of cm2 of papyrus.

Casey’s crackle pattern

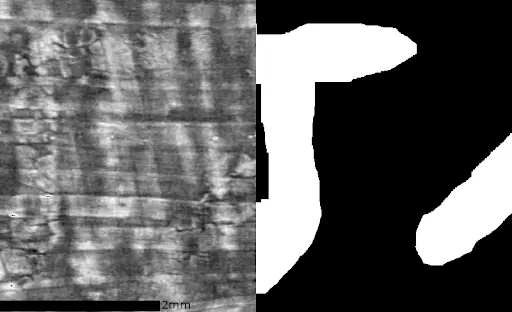

In early August, contestant Casey Handmer, an ex-JPL startup founder and polymath, wrote a blog post about his discovery of a “crackle pattern” that looks like ink.

Casey found the pattern by staring at the segmented CT scans for hours on end. This was a major and surprising discovery. Stephen Parsons had seen direct evidence of ink in detached fragments before, but not yet in the scrolls.

Casey was the first person in 2,000 years to find ink — and a letter — inside an unopened scroll.

Luke Farritor’s model

After this discovery, several contestants looked for more crackle, but it seemed quite rare. Luke Farritor, a college student and SpaceX summer intern working at Starbase, had heard about Vesuvius Challenge from Dwarkesh Patel’s podcast interview with Nat.

He saw Casey’s crackle pattern being discussed in the Discord, and began spending his evenings and late nights training a machine learning model on the crackle pattern. With each new crackle found, the model improved, revealing more crackle in the scroll — a cycle of discovery and refinement.

He found a few dozen ink strokes — and some complete letters — that could be labeled and used as training data.

Before long, the model was unveiling traces of crackle invisible to his own eye. Soon, these traces began to form letters and hints of actual words.

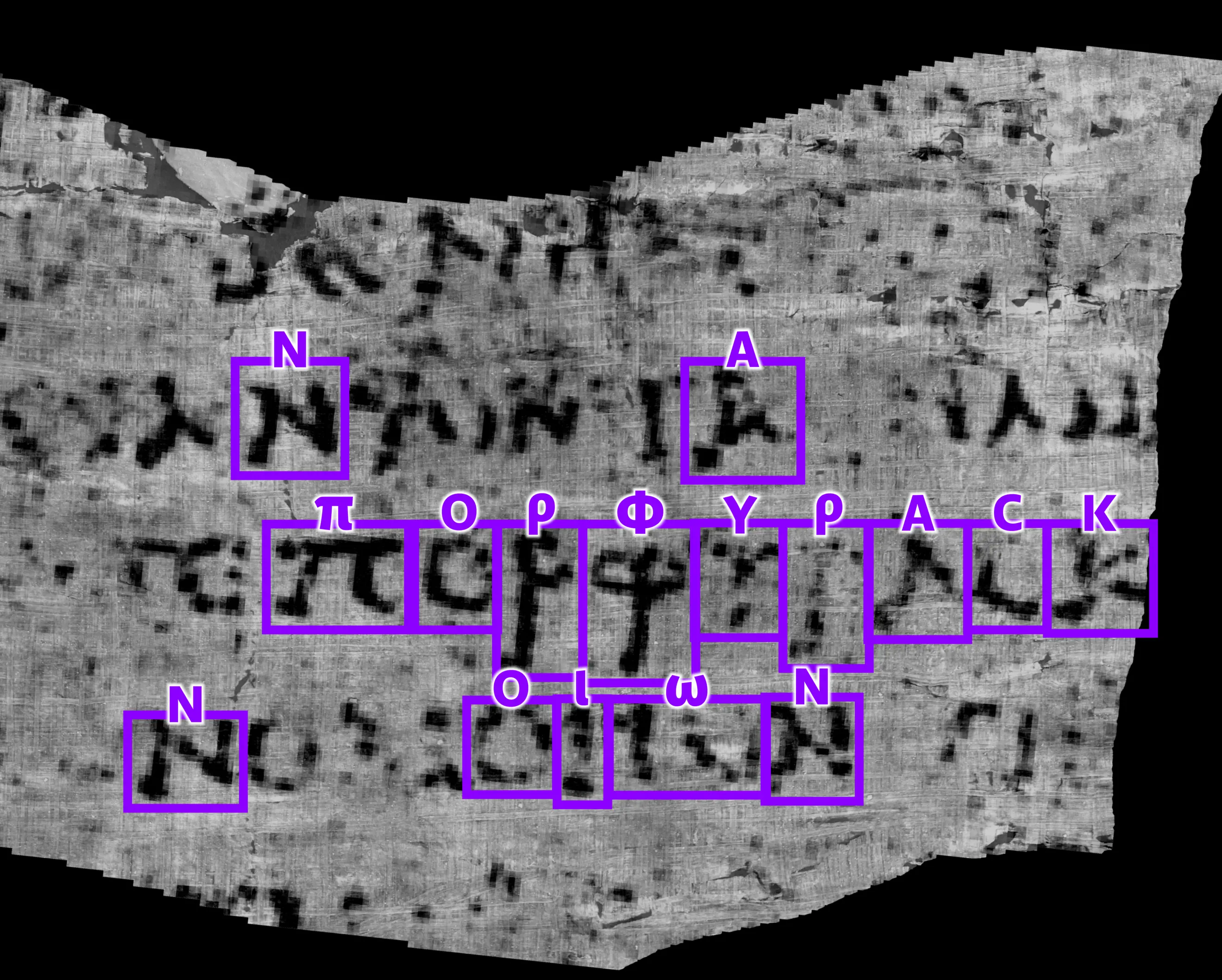

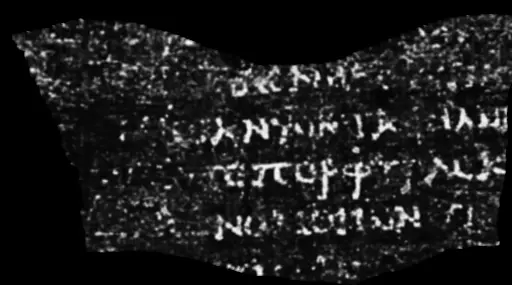

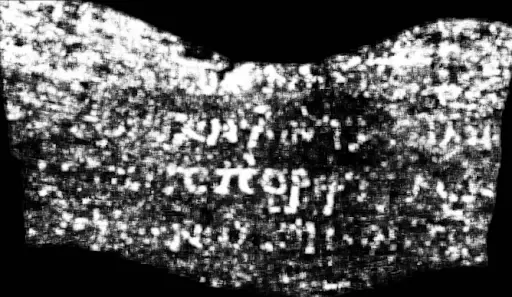

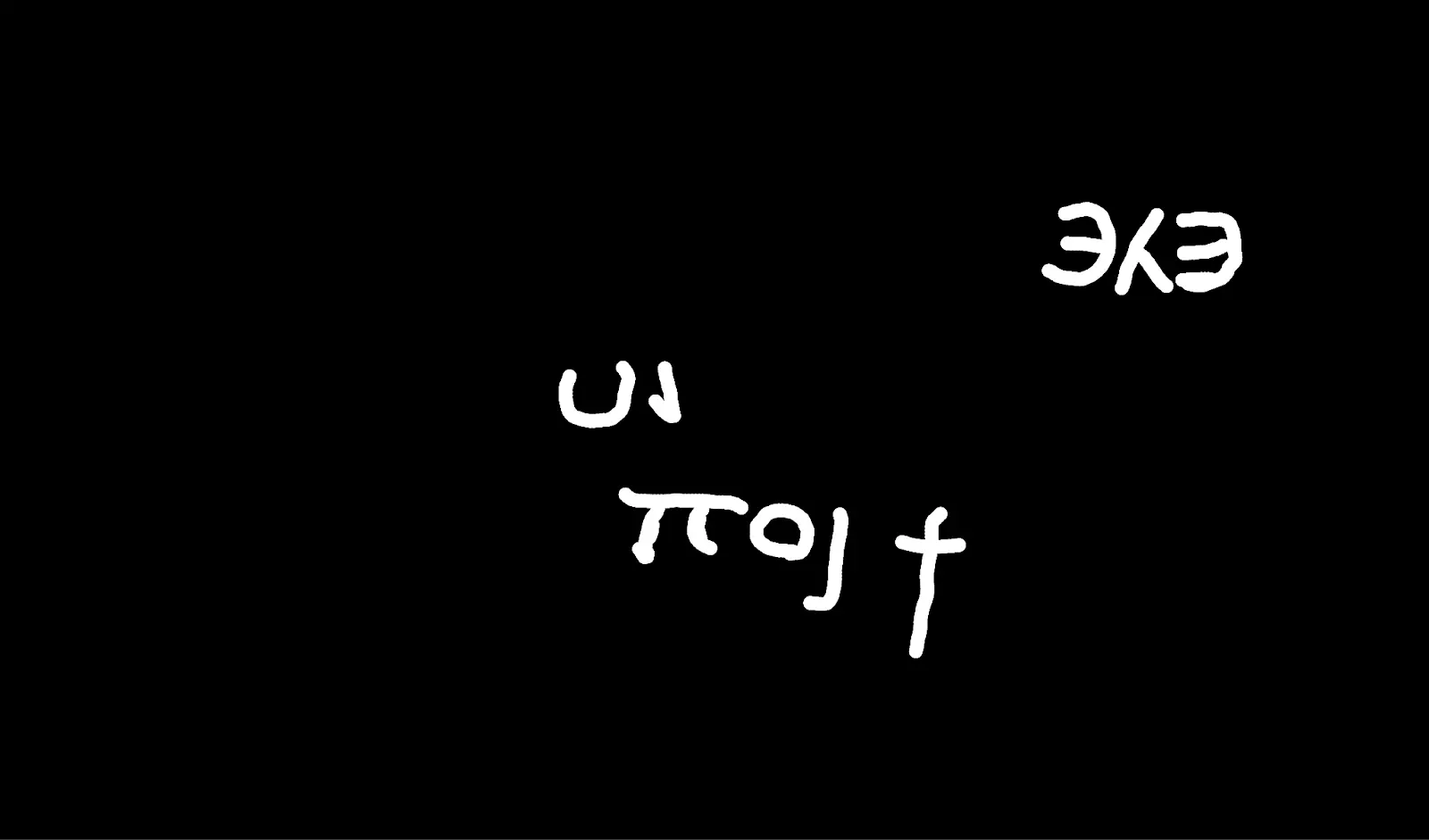

Luke then made a submission to our First Letters Prize, which required contestants to find at least 10 letters in a 4 cm2 area. This was his first submission:

When professor Seales showed this image to our team of papyrologists, scholars specializing in works on papyrus, they gasped: they could immediately read the word “porphyras,” despite the letters being faint.

After thorough technical review, we sent a newer version of his picture to the panel of papyrologists. Independently and unanimously, they annotated 13 letters, albeit with varying levels of confidence:

Indeed, the word held up to scrutiny. “Porphyras” is an exciting word: it means “purple” and is quite rare in ancient texts.

If you’re trying to find these letters in the image, keep in mind that our modern characters look a little bit different. The letters in this ancient script look more like this: ΠΟΡΦΥΡΑϹ. Note that texts from this time didn’t use spaces, making it harder to determine word boundaries.

Luke’s First Letters Prize submission is available now on GitHub.

Youssef’s discovery

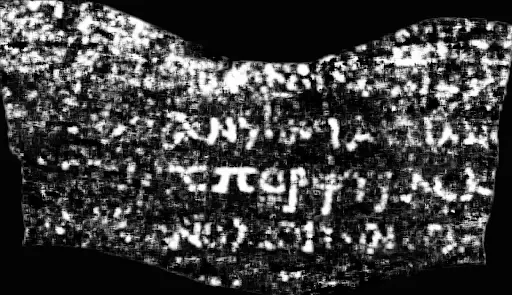

Meanwhile, another contestant, Youssef Nader, an Egyptian biorobotics grad student in Berlin, pursued a different approach. Motivated by Casey and Luke’s findings, he sifted through the winning entries of the Ink Detection prize on Kaggle — which was focused on improving Stephen Parsons’ approach of machine learning in detached fragments. He used a domain transfer technique to adapt these models to the scrolls: unsupervised pretraining on the scroll data, followed by fine-tuning on the fragment labels.

He submitted his idea for an “Ink Detection Followup Prize” and won a small prize. The idea seemed promising, but as far as we knew, that was that. Several weeks later, Youssef made his own submission to the First Letters prize. He had seen Luke’s early results which had been shared on X and Discord and decided to focus on the same area within the scroll.

With this modified model from the Kaggle competition, he managed to find some letters, though entirely without relying on Casey’s method of manually looking for crackle. He then annotated what looked like letter shapes to the label data.

He repeated this pseudo-labeling iteratively, resulting in speculative labels for a number of segments within the scroll. Models trained on these labels were then capable of detecting ink from within the scroll and the training data from the detached scroll fragments were ultimately removed.

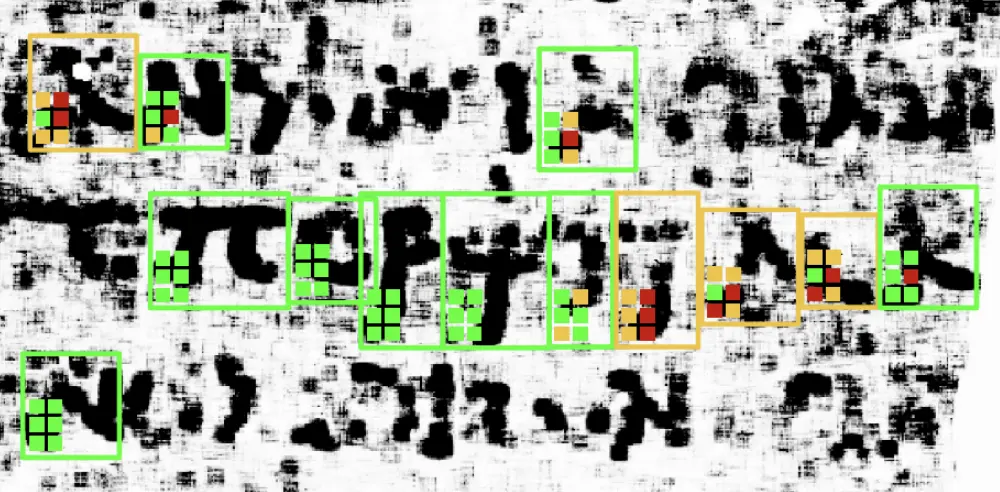

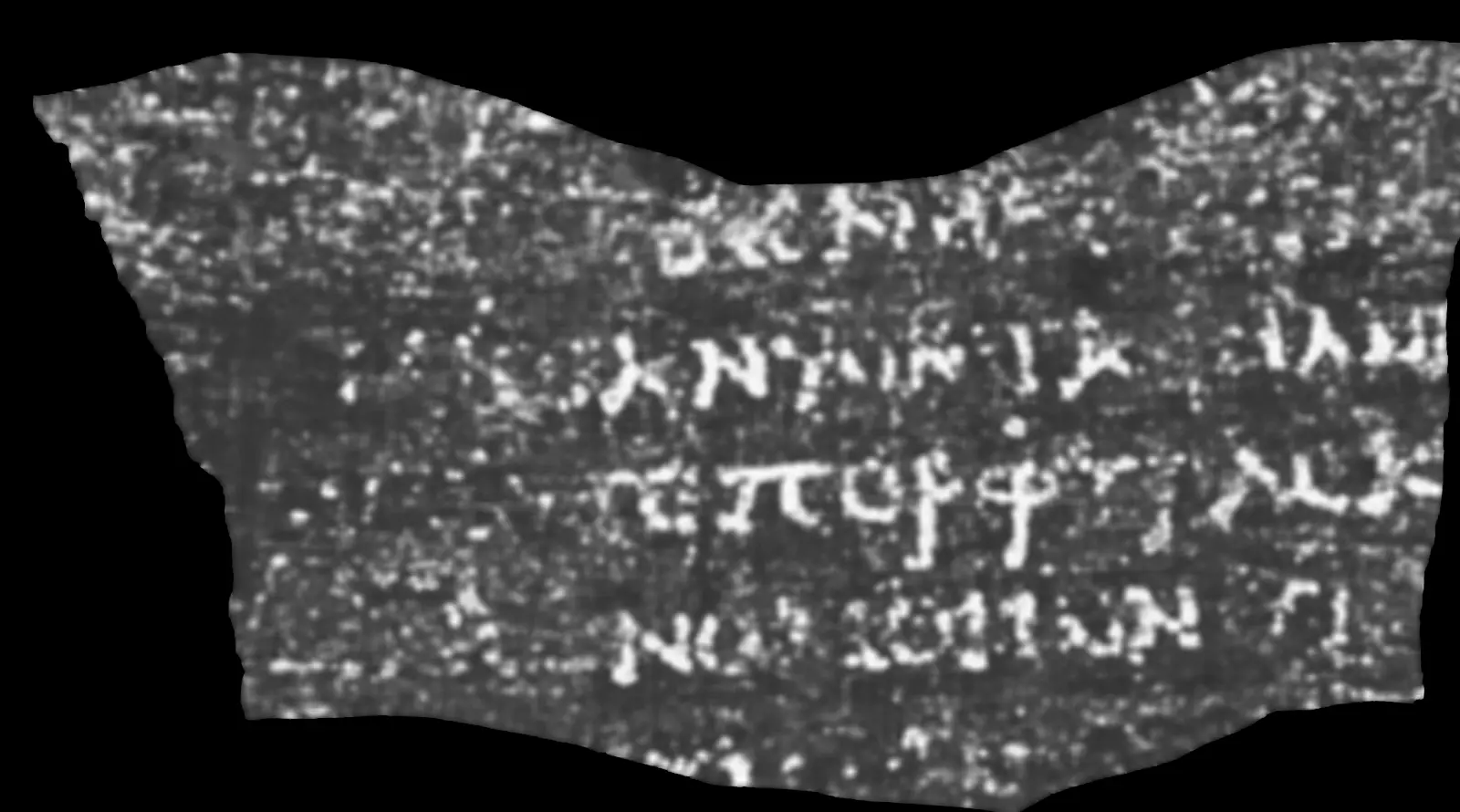

The final models trained solely on internal scroll segments resulted in the image below, securing Youssef the prize.

This time, the papyrologists agreed more strongly about the letters. They even began speculating on possible words above (ανυοντα / ANYONTA, “achieving”) and below (ομοιων / OMOIωN, “similar”).

If these words are indeed what we think they are, this papyrus scroll likely contains an entirely new text, unseen by the modern world.

Youssef’s First Letters Prize submission is available now on GitHub.

Why were we successful?

There were many contributions from different people in the critical path for these discoveries. Our combination of competition and open source (through “progress prizes”) seems to work! To highlight a few key contributions:

- Youssef used a model from the Kaggle competition and was inspired by Luke’s results to look in the same area.

- Luke’s search for crackle was directly inspired by Casey’s work.

- Casey was able to look through many sheets of papyrus because our segmentation team had mapped out hundreds of cm2.

- The segmentation team was able to map out a lot of papyrus because of tooling built by contestants who worked on “Segmentation Tooling Prizes” (work by Julian Schilliger, Chuck, Yao Hsiao, and many others).

- The segmentation tooling advances were possible because contestants built on top of existing open source tools by professor Seales’ team (work by Seth Parker, Stephen Parsons, and many others). And of course, the contest itself wouldn’t have been possible without the foundation that Dr. Seales and his team, along with their funders, have laid out and continue to support.

Looking back at what got us to this point, it seems that almost every single thing we did in running this contest so far has been load-bearing. We’re not quite sure what to make of this! Perhaps that progress is more fragile and success is more contingent than it often seems in retrospect.

What’s next?

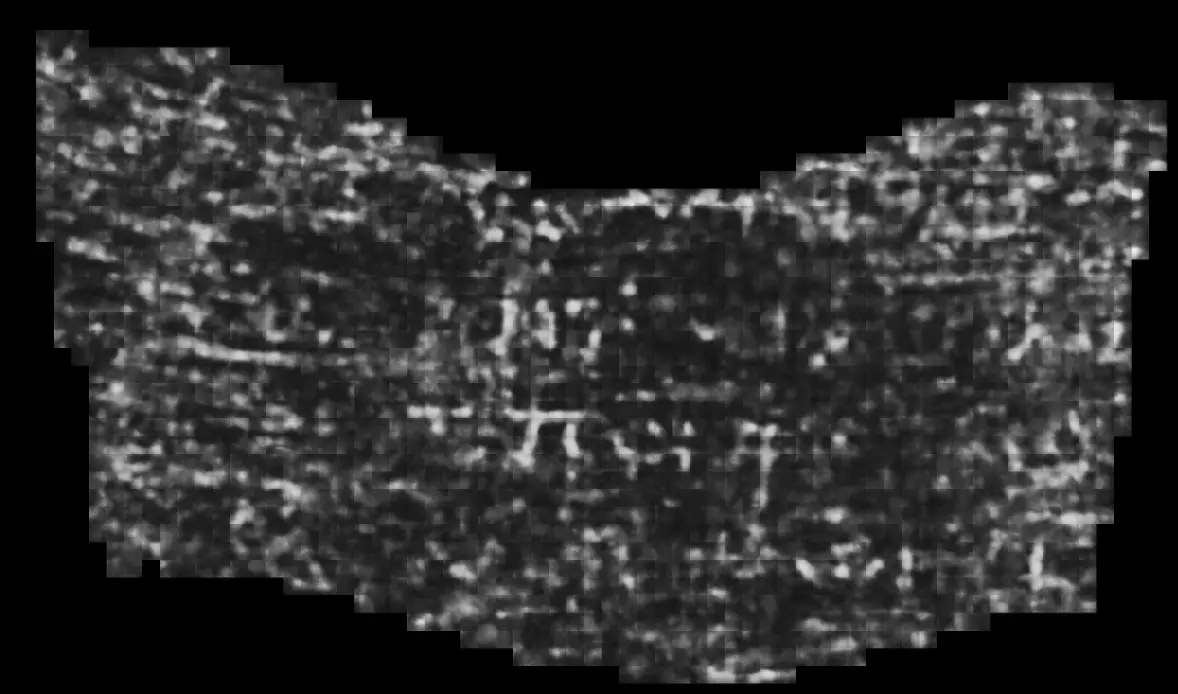

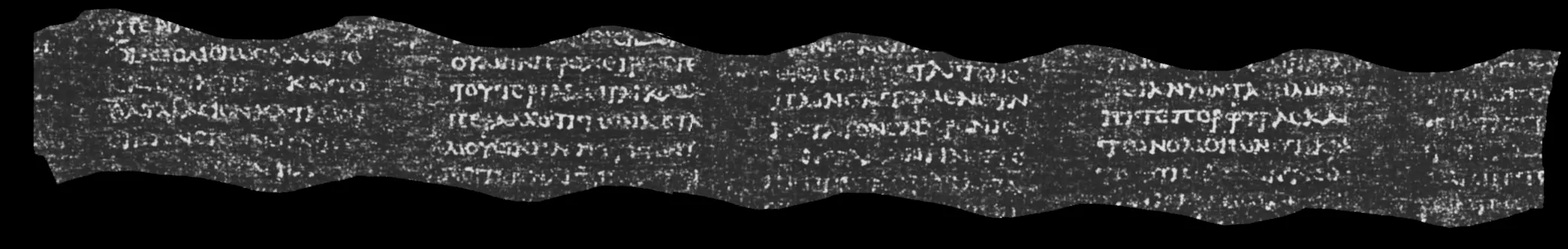

The segmentation team and contestants continue to make progress, and a few days ago Youssef’s model generated a new image of shocking clarity and size:

In this image you can clearly see four and a half columns of text, separated by margins. Many more letters are now visible, though not all are immediately legible. Our papyrological team is working hard to further investigate this result, and we’ll have updates on this soon.

These advancements demonstrate that the $700,000 Grand Prize is within reach. Our optimism is at an all time high.

Now is the best time to get involved! Join our vibrant Discord community, sign up to receive newsletters via Substack, or follow @scrollprize on X. To get started, download some data, walk through some of our tutorials, and catch up on the progress made by contestants by looking at the prize winners and community tools.

Will you be the one unlocking the knowledge in hundreds of scrolls — doubling the amount of texts from antiquity — and potentially thousands more that are yet to be excavated, becoming the last hero of the Roman Empire and winning $700,000 while you’re at it?

The race is on.